Keeping Wheat Alive

For thousands of years, we’ve been growing wheat for food, carefully selecting plants that will thrive in different climates and environments, while providing the nutrition and flavor we want. When we bake bread, cakes and cookies, we use this modern, cultivated wheat.

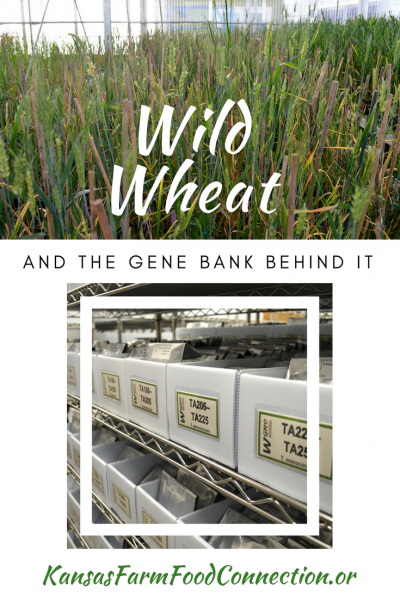

But there are wild varieties of wheat across the globe that can be traced back even further. And in the heart of Kansas is a gene bank dedicated to preserving and studying these wild relatives. Why?

Crops are constantly under threat from weather, pests and disease. Not only can blight devastate an entire crop, it can also threaten food production in a given area for years. If plants aren’t resistant to the threat in question, they can’t survive.

Scientists and plant breeders can crossbreed wheat for numerous traits to help combat susceptibility to threats, while still tasting great. But sometimes desired traits can’t be found in common varieties, so they turn to wild relatives. But, how can they access that gene pool? Where can scientists find ancient and rarely cultivated varieties that just might solve a really important problem?

Enter the Wheat Genetic Resource Center, part of the Wheat Innovation Center in Manhattan.

The center’s gene bank houses 3,800 wild lines of wheat found around the world from Morocco, Southern Spain, the Mediterranean, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Russia, Afghanistan and China.

Stored in a well-organized system and highly controlled climate, these seeds are catalogued, bred, studied and sometimes end up in our cultivated plants.

We caught up with Jon Raupp, senior research scientist, who oversees the gene bank, to learn more about the work he does.

If breeders need a crossbreed to include a particular trait, like stem rust fungus resistance, they can request access to the wild varieties for testing. That means the seeds in the bank must be viable. That’s where Jon comes in.

“My main job is keeping the wild lines alive so we can help the breeding community,” Jon says. “I very much enjoy working with these plants and keeping the gene bank going.”

Jon periodically checks the seeds to see when they were last grown. If it’s been awhile, he plants them in the greenhouses at the Wheat Innovation Center to make sure they can still produce. He’s been working at the gene bank since 1980 and has seen a lot of technological advancement over the years.

“When I started in this business, the science was a lot different,” he says. “There was nothing at the DNA level — you couldn’t sequence like you can now.”

Still, the process — all the way from identifying traits in a plant to introducing a new line — can take years. And it requires a big team effort to happen.

“We have 20 scientists in the lab doing molecular work. Everybody’s work intertwines to give you the final result,” Jon says. “When you finally release a line that you can give to breeders that has a gene you’ve discovered, that’s rewarding.”

When one season can threaten food production for years, time is of the essence. Wheat breeders plan about 15 years out, looking ahead to determine likely threats and finding varieties that will grow in the changing environment. Then they have to produce enough of the seed for farmers to plant. Having a resource like the gene bank in the United States means they can access these wild strains and help defend against threats.

“It’s like a domino effect,” Jon says. “In order for farmers to grow wheat under the pressures the environment puts on a crop, they’ll need breeders to supply them with cultivars that can grow in these conditions. The breeders will need genes to make the supply. We’re at the beginning of that journey.”

And at the end of that journey are people like you and me — who turn to wheat products to feed our families.